In 2015, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) promulgated the Clean Power Plan rule, which addressed carbon dioxide emissions from existing coal- and natural-gas-fired power plants. For authority, the Agency cited Section 111 of the Clean Air Act, which, although known as the New Source Performance Standards program, also au- thorizes regulation of certain pollutants from existing sources under Section 111(d). 42 U. S. C. §7411 Prior to the Clean Power Plan, EPA had used Section 111(d) only a handful of times since its enact- ment in 1970. Under that provision, although the States set the actual enforceable rules governing existing sources (such as power plants), EPA determines the emissions limit with which they will have to com- ply. The Agency derives that limit by determining the “best system of emission reduction . . . that has been adequately demonstrated,” or the BSER, for the kind of existing source at issue. §7411(a)(1). The limit then reflects the amount of pollution reduction “achievable through the application of” that system. Ibid.

buildings, that had never before been subject to such re- quirements. Id., at 310, 324. We declined to uphold EPA’s claim of “unheralded” regulatory power over “a significant portion of the American economy.” Id., at 324. In Gonzales v. Oregon, 546 U. S. 243 (2006), we confronted the Attorney General’s assertion that he could rescind the license of any physician who prescribed a controlled substance for as- sisted suicide, even in a State where such action was legal. The Attorney General argued that this came within his statutory power to revoke licenses where he found them “in- consistent with the public interest,” 21 U. S. C. §823 We considered the “idea that Congress gave [him] such broad and unusual authority through an implicit delegation . . . not sustainable.” 546 U. S., at 267. Similar considerations informed our recent decision invalidating the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s mandate that “84 mil- lion Americans . . . either obtain a COVID–19 vaccine or un- dergo weekly medical testing at their own expense.” Na- tional Federation of Independent Business v. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 595 U. S. ___, ___ (2022) (per curiam) (slip op., at 5). We found it “telling that OSHA, in its half century of existence,” had never relied on its au- thority to regulate occupational hazards to impose such a remarkable measure. Id., at ___ (slip op., at 8).

- The Supreme Court has ruled on the subject of a 2015 Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rule called the Clean Power Plan rule, which would force operators to "shift" to cleaner forms of energy.

- The EPA justified the rule using the 1970 Clean Air Act which gives the agency authority to regulate carbon emissions for existing power plants.

- The emission limits would have required power plants to reduce power output, invest in clean energy, or purchase emission allowance credits.

The Supreme Court, after bouncing around the court systems during three presidential administrations, has struck down an Obama-era EPA regulation known as the Clean Power Plan (CPP) in a 6-3 decision. The rule required power plants to drastically reduce their carbon dioxide emissions.

The majority was made up of six conservative justices, with three liberal justices dissenting. The majority ruled against the plan citing the "major questions doctrine," which resolves that Congress must approve of laws that have "great political or economic significance." The dissent noted that the carbon emission goals outlined in the Clean Power Plan were still reached without the plan ever being implemented, suggesting that the regulation was not all that economically significant.

The EPA is in charge of determining the emissions limit with which power sources must comply, with states developing a plan to enforce that limit. The agency determines this limit by finding the "best system of emission reduction... that has been adequately demonstrated," for a certain type of power source. This comes from a 1970 law called the Clean Air Act, specifically a provision called the New Source Performance Standards program or Section 111, which mostly deals with regulating newly-built power source standards, hence the name. However, this provision also authorizes regulation of certain pollutants in existing power plants.

The EPA determined that the "best system of emission reduction" for coal and natural gas power plants would be to transition these plants to cleaner sources of energy using "generation shifting."

They determined three measures they called "building blocks." The three building blocks were:

- Heat rate improvements for coal-fire plants, practices such plants could take to burn coal more cleanly.

- A shift from coal-fire power plants to natural-gas-fire power plants.

- A shift from natural-gas-fire power plants to renewable energy sources like wind and solar.

Building block 1 is uncontroversial. Building blocks 2 and 3, however, are markedly different than guidelines issued by the EPA in the past in that it involved "generation shifting," like the transition from coal to natural gas, or natural gas to wind.

The agency explained that power plant operators could fulfill these requirements by doing one or a combination of the following:

- Reduce production of electricity.

- Build or invest in new or existing natural gas plant, wind farm, or solar installation.

- Purchase emission allowance or credits as a cap-and-trade regime (carbon credits)

The EPA based these new carbon limits on the assumption that power plant owners would have to transition away from coal and natural gas by 1) reducing the amount of energy they produced 2) investing in clean energy, or 3) purchasing "carbon credits," tradable emission allowances that are limited in number.

The Majority Opinion

In the majority opinion, Chief Justice Roberts points out that the "emissions limit the Clean Power Plan established for existing power plants was actually stricter than the cap imposed by the simultaneously published standards for new plants." He continued, "The point, after all, was to compel the transfer of power generating capacity from existing sources to wind and solar."

The court also cites the EPA's own modeling, which predicted that the rule would "entail billions of dollars in compliance costs (to be paid in the form of higher energy prices), require the retirement of dozens of coal-fired plants, and eliminate tens of thousands of jobs across various sectors."

Chief Justice Roberts: Opinion of the Court

The Agency nodded to the novelty of its approach when it explained that it was pursuing a 'broader, forward-thinking approach to the design' of Section 111 regulations that would “improve the overall power system,” rather than the emissions performance of individual sources, by forcing a shift throughout the power grid from one type of energy source to another.

Chief Justice Roberts: Opinion of the Court

[The major questions doctrine] took hold because it refers to an identifiable body of law that has developed over a series of significant cases all addressing a particular and recurring problem: agencies asserting highly consequential power beyond what Congress could reasonably be understood to have granted. Scholars and jurists have recognized the common threads between those decisions. So have we.

Chief Justice Roberts: Opinion of the Court

Under our precedents, this is a major questions case. In arguing that Section 111(d) empowers it to substantially restructure the American energy market, EPA “claim[ed] to discover in a long-extant statute an unheralded power” representing a “transformative expansion in [its] regulatory authority.” Utility Air, 573 U. S., at 324. It located that newfound power in the vague language of an “ancillary provision[ ]” of the Act, Whitman, 531 U. S., at 468, one that was designed to function as a gap filler and had rarely been used in the preceding decades. And the Agency’s discovery allowed it to adopt a regulatory program that Congress had conspicuously and repeatedly declined to enact itself.

The court points out that Congress itself has been unable to pass a bill with provisions similar to the Clean Power Plan and therefore did not likely intend for the EPA to have this power.

Chief Justice Roberts: Opinion of the Court

Under the Agency’s prior view of Section 111, its role was limited to ensuring the efficient pollution performance of each individual regulated source. Under that paradigm, if a source was already operating at that level, there was nothing more for EPA to do. Under its newly “discover[ed]” authority, Utility Air, 573 U. S., at 324, however, EPA can demand much greater reductions in emissions based on a very different kind of policy judgment: that it would be “best” if coal made up a much smaller share of national electricity generation. And on this view of EPA’s authority, it could go further, perhaps forcing coal plants to “shift” away virtually all of their generation—i.e., to cease making power altogether.

Chief Justice Roberts: Opinion of the Court

(“Even if Congress has delegated an agency general rule- making or adjudicatory power, judges presume that Congress does not delegate its authority to settle or amend major social and economic policy decisions.”). Congress certainly has not conferred a like authority upon EPA any- where else in the Clean Air Act. The last place one would expect to find it is in the previously little-used backwater of Section 111(d).

Chief Justice Roberts: Opinion of the Court

The dissent contends that there is nothing surprising about EPA dictating the optimal mix of energy sources nationwide, since that sort of mandate will reduce air pollution from power plants, which is EPA’s bread and butter. Post, at 20–22. But that does not follow. Forbidding evictions may slow the spread of disease, but the CDC’s ordering such a measure certainly “raise[s] an eyebrow.” Post, at 18. We would not expect the Department of Homeland Security to make trade or foreign policy even though doing so could decrease illegal immigration. And no one would consider generation shifting a “tool” in OSHA’s “toolbox,” post, at 21, even though reducing generation at coal plants would reduce workplace illness and injury from coal dust.

Chief Justice Roberts: Opinion of the Court

Finally, we cannot ignore that the regulatory writ EPA newly uncovered conveniently enabled it to enact a program that, long after the dangers posed by greenhouse gas emissions “had become well known, Congress considered and rejected” multiple times.

The court refers to Section 111, the provision the EPA used for justification that grants the agency the authority to cap levels of emission reflecting “the application of the best system of emission reduction . . . adequately demonstrated.”

Chief Justice Roberts: Opinion of the Court

As a matter of “definitional possibilities,” FCC v. AT&T Inc., 562 U. S. 397, 407 (2011), generation shifting can be described as a “system”—“an aggregation or assemblage of objects united by some form of regular interaction,” Brief for Federal Respondents 31—capable of reducing emissions. But of course almost anything could constitute such a “system”; shorn of all context, the word is an empty vessel. Such a vague statutory grant is not close to the sort of clear authorization required by our precedents.

Chief Justice Roberts: Opinion of the Court

Capping carbon dioxide emissions at a level that will force a nationwide transition away from the use of coal to generate electricity may be a sensible “solution to the crisis of the day.” New York v. United States, 505 U. S. 144, 187 (1992). But it is not plausible that Congress gave EPA the authority to adopt on its own such a regulatory scheme in Section 111(d). A decision of such magnitude and consequence rests with Congress itself, or an agency acting pursuant to a clear delegation from that representative body. The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit is reversed, and the cases are remanded for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

The Court also states that while the Clean Power Plan may be a viable solution to reducing carbon emissions, only Congress has the authority to enact such a plan.

The Dissent

Justice Kagan: Dissenting

Today, the Court strips the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) of the power Congress gave it to respond to “the most pressing environmental challenge of our time.” Massachusetts v. EPA, 549 U. S. 497, 505 (2007).

Climate change’s causes and dangers are no longer subject to serious doubt. Modern science is “unequivocal that human influence”—in particular, the emission of green- house gases like carbon dioxide—“has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land.” Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Sixth Assessment Report, The Physical Science Basis: Headline Statements 1 (2021). The Earth is now warmer than at any time “in the history of modern civilization,” with the six warmest years on record all occur- ring in the last decade. U. S. Global Change Research Pro- gram, Fourth National Climate Assessment, Vol. I, p. 10 (2017); Brief for Climate Scientists as Amici Curiae 8. The rise in temperatures brings with it “increases in heat- related deaths,” “coastal inundation and erosion,” “more frequent and intense hurricanes, floods, and other extreme weather events,” “drought,” “destruction of ecosystems,” and “potentially significant disruptions of food production.”

Justice Kagan: Dissenting

Congress charged EPA with addressing those potentially catastrophic harms, including through regulation of fossil- fuel-fired power plants. Section 111 of the Clean Air Act directs EPA to regulate stationary sources of any substance that “causes, or contributes significantly to, air pollution” and that “may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.” 42 U. S. C. §7411(b)(1)(A). Carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases fit that description.

Justice Kagan: Dissenting

To carry out its Section 111 responsibility, EPA issued the Clean Power Plan in 2015. The premise of the Plan— which no one really disputes—was that operational improvements at the individual-plant level would either “lead to only small emission reductions” or would cost far more than a readily available regulatory alternative. 80 Fed. Reg. 64727–64728 (2015). That alternative—which fossil- fuel-fired plants were “already using to reduce their [carbon dioxide] emissions” in “a cost effective manner”—is called generation shifting. Id., at 64728, 64769. As the Court ex- plains, the term refers to ways of shifting electricity generation from higher emitting sources to lower emitting ones— more specifically, from coal-fired to natural-gas-fired sources, and from both to renewable sources like solar and wind. See ante, at 8. A power company (like the many sup- porting EPA here) might divert its own resources to a cleaner source, or might participate in a cap-and-trade system with other companies to achieve the same emissions- reduction goals.

Justice Kagan: Dissenting

This Court has obstructed EPA’s effort from the beginning. Right after the Obama administration issued the Clean Power Plan, the Court stayed its implementation. That action was unprecedented: Never before had the Court stayed a regulation then under review in the lower courts. See Reply Brief for 29 States and State Agencies in No. 15A773, p. 33 (conceding the point). The effect of the Court’s order, followed by the Trump administration’s repeal of the rule, was that the Clean Power Plan never went into effect. The ensuing years, though, proved the Plan’s moderation.

Justice Kagan: Dissenting

So by the time yet another President took office, the Plan had become, as a practical matter, obsolete. For that reason, the Biden administration announced that, instead of putting the Plan into effect, it would commence a new rulemaking. Yet this Court determined to pronounce on the legality of the old rule anyway. The Court may be right that doing so does not violate Article III mootness rules (which are notoriously strict). See ante, at 14–16. But the Court’s docket is discretionary, and because no one is now subject to the Clean Power Plan’s terms, there was no reason to reach out to decide this case. The Court today issues what is really an advisory opinion on the proper scope of the new rule EPA is considering. That new rule will be subject anyway to immediate, pre-enforcement judicial review. But this Court could not wait—even to see what the new rule says—to constrain EPA’s efforts to address climate change.

Justice Kagan: Dissenting

The limits the majority now puts on EPA’s authority fly in the face of the statute Congress wrote. The majority says it is simply “not plausible” that Congress enabled EPA to regulate power plants’ emissions through generation shifting. Ante, at 31. But that is just what Congress did when it broadly authorized EPA in Section 111 to select the “best system of emission reduction” for power plants. §7411(a)(1). The “best system” full stop—no ifs, ands, or buts of any kind relevant here. The parties do not dispute that generation shifting is indeed the “best system”—the most effective and efficient way to reduce power plants’ car- bon dioxide emissions. And no other provision in the Clean Air Act suggests that Congress meant to foreclose EPA from selecting that system; to the contrary, the Plan’s regulatory approach fits hand-in-glove with the rest of the statute. The majority’s decision rests on one claim alone: that generation shifting is just too new and too big a deal for Congress to have authorized it in Section 111’s general terms.

Justice Kagan: Dissenting

A key reason Congress makes broad delegations like Section 111 is so an agency can respond, appropriately and commensurately, to new and big problems. Congress knows what it doesn’t and can’t know when it drafts a statute; and Congress therefore gives an expert agency the power to address issues—even significant ones—as and when they arise. That is what Congress did in enacting Section 111. The majority today overrides that legislative choice. In so doing, it deprives EPA of the power needed—and the power granted—to curb the emission of greenhouse gases.

Justice Kagan: Dissenting

Section 111(d) thus ensures that EPA regulates existing power plants’ emissions of all pollutants. When the pollutant at issue falls within the NAAQS or HAP programs, EPA need do no more. But when the pollutant falls outside those programs, Section 111(d) requires EPA to set an emissions level for currently operating power plants (and other stationary sources). That means no pollutant from such a source can go unregulated: As the Senate Report explained, Section 111(d) guarantees that “there should be no gaps in control activities pertaining to stationary source emissions that pose any significant danger to public health or welfare.”

Justice Kagan: Dissenting

The majority complains that a similar definition—cited to the Solicitor General’s brief but originally from another dictionary—is just too darn broad. Ante, at 28; see Brief for United States 31 (quoting Webster’s New International Dictionary 2562 (2d ed. 1959)). “[A]lmost anything” capable of reducing emissions, the majority says, “could constitute such a ‘system’ ” of emission reduction. Ante, at 28. But that is rather the point. Congress used an obviously broad word (though surrounding it with constraints, see supra, at 7) to give EPA lots of latitude in deciding how to set emissions limits. And contra the majority, a broad term is not the same thing as a “vague” one. Ante, at 18, 20, 28. A broad term is comprehensive, extensive, wide-ranging; a “vague” term is unclear, ambiguous, hazy. (Once again, dictionaries would tell the tale.) So EPA was quite right in stating in the Clean Power Plan that the “[p]lain meaning” of the term “system” in Section 111 refers to “a set of measures that work together to reduce emissions.” 80 Fed. Reg. 64762. Another of this Court’s opinions, involving a matter other than the bogeyman of environmental regulation, might have stopped there.

What power does the EPA have?

The EPA has the authority to make laws and regulations because Congress, the legislative branch of government, has granted them that authority. This is called statutory delegation.

By defining the precise area for which the agency is permitted to draft laws, Congress can grant regulatory authority to a given agency. Agencies like the EPA are part of the executive branch, which is responsible for executing and enforcing law, and thus only have the authority to create legislation that is precisely within the authority granted to it.

One of the Supreme Court's roles is to prevent an agency from going beyond its authority, so Congress must be very clear about what these agencies can and cannot do. The more precise Congress' language, the less likely a court will intervene. Congresspeople who wish to grant agencies more power try to pass legislation with broad language, hoping they will pass the court's test, while other congresspeople prefer to use very specific and benign language, reserving large legislative changes to be passed by Congress alone.

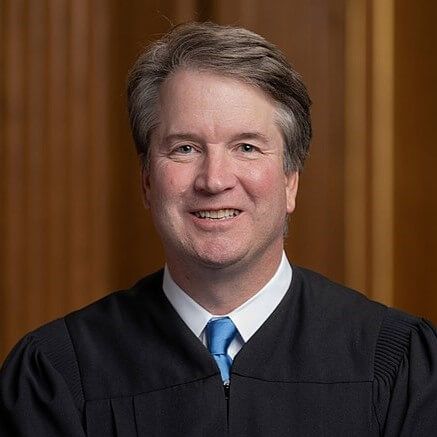

While Congress is composed entirely of elected representatives, agencies are made up of unelected employees. Given that Congress is the only branch of government with the legal authority to pass laws, it is unclear whether the executive branch should be given broad legislative authority under the Constitution. From this comes the legal basis for the "major questions doctrine," the main justification for the court's EPA ruling. Justice Kavanaugh summarizes the basis for the rule:

Then Appeals Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh

For an agency to issue a major rule, Congress must clearly authorize the agency to do so. If a statute only ambiguously supplies authority for the major rule, the rule is unlawful.

Limitations of Statutory Delegation

The main problem with statutory delegation is that executive branch regulations are easily overturned, either by a court or by a subsequent presidential administration. For example, the Obama-era EPA issued the Clean Power Plan in 2015, which was quickly repealed by the Trump administration in 2018. The president is the head of the executive branch and technically has authority over the agencies that operate within it, though like with Trump's repeal of the Clean Power Plan, it can take a couple of years.

Agencies are not always responsive to the president's wishes. Government agencies are bureaucracies with a large number of employees and complex governance systems. This means that unchecked agencies can operate for a long time without oversight from any elected official. The path to the top of administrative offices in these agencies, like the path to Congress or the presidency, is highly political and can deviate from the organization's prescribed purpose.

Recently the Supreme Court has been particularly skeptical of agency authority to regulate matters of national importance without a clear mandate from Congress. The Supreme Court ruled that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) did not have the authority to impose a nationwide eviction moratorium, and that the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) did not have the authority to issue a broad vaccine mandate.

So what?

This ruling is a major blow to President Biden who now has limited options when it comes to climate change. Without the avenue of agency regulation, Biden needs to gather support for an energy bill in Congress if he hopes to complete any of his climate agenda.

A chance for a meaningful bill of that type in Congress, however, is looking slim. Democrats have been negotiating with Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV), a moderate holdout, trying to get his vote for a major fossil fuels bill without which has no chance of passing. He recently stated there was no version of the bill that we was willing to vote for, claiming that it would kill the coal industry in his home state of West Virginia, cost the state hundreds of millions of dollars and tens of thousands of jobs.

One of Biden's campaign promises was pursuing climate change regulation. His only options now are passing a much less aggressive (and probably benign) energy bill, or issuing a series of executive orders.

With slim majorities in Congress, the Biden administration finally convinced Senator Manchin to join an energy and healthcare bill. Before this bill, Biden announced his intention of issuing a series of executive orders to combat climate change.

The bottom line

The court determined that the EPA exceeded the authority granted to it by Congress. In other words, the Clean Power Plan may be a good idea, but it must be approved by Congress.

Simply put, the path to substantive carbon emission regulation begins with Congress and ends with the president signing it.